Catch the IPL scandal in a nutshell

• How big is the IPL business? Difficult to estimate. Optimists reckon the revenue earnings of the BCCI and the 8 teams would be a little over Rs 2,000 crore this season. With TV advertising revenues, it would swell to around Rs 2,700 crore. The revenues of the BCCI and the 8 teams would put IPL on a par with Glaxosmithkline Pharmaceuticals (Rs 2,057 crore last year) and above Vijay Mallya’s United Breweries (Rs 1,983 crore)

• What is the BCCI’s share in this (is this equal to a small, medium or large business’s revenues)? The BCCI stands to earn around Rs 1,170 crore. It must fork out about Rs 620 crore to the 8 teams as their share from the central pool of revenues. It will pay out another Rs 33 crore as prize money and umpire salaries. This will leave it with a non-taxable income of around Rs 517 crore. In terms of profits from the IPL, the BCCI would rank on a par with Glaxosmithkline (Rs 500.46 crore last year) and much higher than Videocon Industries (Rs 415 crore)

• What is the franchises’ share? The teams will get to split about Rs 950 crore — which is roughly Rs 120 crore for each franchise on an average. Teams like the Chennai Super Kings, the Mumbai Indians and the Kolkata Knight Riders should be able to get sizeable revenues from sponsorships, ticket sales and merchandise

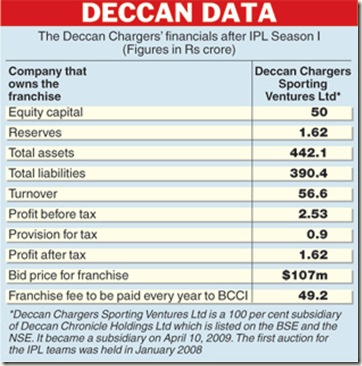

• How much did the promoter stump up? KKR co-owner Shah Rukh Khan, for example, paid Rs 14 crore, a fraction of what it cost to make My Name is Khan. Mukesh Ambani, Vijay Mallya, India Cements, Deccan Chronicle Holdings and GMR — which hold the entire stake in their teams — will have to fork out more. But the other teams have several co-owners and the amount each will have to put up will be much lower. The ownership pattern in some teams isn’t clear because of suspicion that there may be a layered shareholding structure leading to indirect stakes in the team. This will further reduce the burden on the people generally regarded as the owners

• Is it right for BCCI members/office-bearers to own IPL franchises, directly or indirectly? There is a possibility for a conflict of interests. N. Srinivasan, the BCCI secretary, is MD of India Cements, which won the Chennai franchise. BCCI regulations do not permit any administrator to have, directly or indirectly, any commercial interest in matches or events conducted by the board. But the BCCI, in September 2008, amended the regulations through clause 6.2.4 that took the IPL and other T20 tournaments out of the ambit of this regulation. The amendment has been challenged in court

• There is talk about companies that own the franchises having been registered in tax havens like Mauritius? Is that illegal? No. But there are doubts over transparency. If the structure had been clearly declared, there would have been no problem. There is some suspicion that the identities of the real owners of some teams are concealed in this maze of trans-border companies

• What do tax havens offer? They help people minimise their tax burden. Certain tax treaties between India and other countries, known as double-taxation avoidance agreements, allow entrepreneurs to set up companies in India and repatriate profits without having to pay high taxes here. Companies owned by an Indian pay a corporate tax of 34.5% here; those owned by foreigners pay as much as 40%. Tax havens like the Cayman Islands and Bahamas have no income tax, corporation tax, inheritance tax, capital gains or gift tax

• There is also talk of money coming in from banks in Mauritius and other foreign countries. Is that illegal? No. Mauritius has emerged as the biggest springboard for investments into India. Between 2000 and 2009, 44% of all foreign investment into India was routed via Mauritius. Singapore ranks second with 9%. The reason is the double-taxation treaty India has with Mauritius. Mauritius has negotiated similar agreements with other countries, including tax havens, which allow foreign investors to take their money out of the country without paying more than 3% as tax. As long as they can prove they are tax-paying entities there, the entities or persons do not have to pay tax in India. It is a legitimate tax-reducing device but has been much abused. Lately, some foreign investment proposals have been rejected because of “treaty shopping”

• Some of the investments routed through the tax havens are paltry, as low as Rs 9 crore in some cases. Why use havens if tax savings are inconsequential? The suspicion is not about the money coming in but about the money going out. Also, the needle points to the documentation of some of these companies registered in the tax havens

• What then is the problem with the IPL? The apparent lack of transparency in its dealings. Some IPL governing council members have alleged that Lalit Modi did not take the council into confidence and entered into agreements unilaterally

• Why is Lalit Modi being put in the dock? Suspicion, unconfirmed so far, that he owns stakes in some of the franchises through friends and relatives. Modi’s brother-in-law Suresh Chellaram, for example, holds majority stake in the company that owns the Rajasthan Royals. Modi’s stepson-in-law Gaurav Burman owns a stake in Kings XI Punjab. Companies owned by Modi’s friends and relatives have come to own IPL online rights through a web of deals

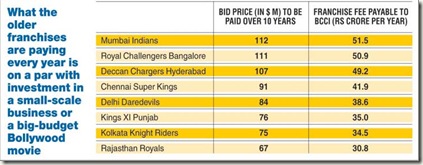

• What was Modi’s role in the team auction? Why the cloud on the bidding? Again, there is suspicion — unconfirmed — that the process was not designed to extract the best price. It was a process to create a closed club of preferred people. Modi, the suspicions are, was looking to pick and choose (as far as he could) the people who would own the clubs. That is why the bids were low for Jaipur, Calcutta and Punjab

• What are MSM and WSG? Why is the broadcast deal under a cloud? Multi Screen Media (MSM), formerly Sony Entertainment Television, holds the telecast rights for the IPL which it bagged for $1.02 billion for 10 years in 2008. The deal was later scrapped by the BCCI, which renegotiated with MSM for a nine-year deal for $1.63 billion. Tax sleuths are focusing on a “facilitation fee” of $80 million (about Rs 356 crore) which MSM paid the Mauritius arm of World Sports Group, the marketing agency of the IPL. MSM says the fee was paid to WSG to give up its broadcast rights for the Indian subcontinent, thus paving the way for the BCCI and MSM to enter into a direct deal. The suspicion is that the money was routed back to India to be paid as kickbacks to top people associated with the IPL

• What might the govt investigation be looking for? Financial irregularities, routing of slush funds through tax havens

• What has the BCCI accused Modi of? The allegations relate to the Rajasthan Royals and Kings XI Punjab bids at the 2008 team auction; the broadcasting deal with MSM; the team auction this year; the allotment of Internet rights of the IPL; and the behaviour of Modi